With US and UK strikes on Houthis in the headlines and Taiwanese voting in their flashpoint election, Group Chief Economist Neil Shearing unpicks what the now- clichéd idea that we live in a “more dangerous world” actually means for thinking through macro risk.

He discusses with David Wilder our framework for looking at a world that’s fracturing into competing economic blocs and what this means for globalisation, as well as how the US election outcome in November could radically shift the narrative.

Neil also previews the coming week’s UK CPI release and explains what it could mean for the timing of rate cuts and talks about what the return of bond vigilantes means for governments in a higher rate world.

Plus, last year was a watershed moment for the global energy market as the US became the largest exporter of LNG. Bill Weatherburn from our Commodities team has just completed five-year forecasts which show another 60% surge in US energy net exports.

He tells David what will drive the surge, discusses the potential impact of November’s election and what this all means for the global economy.

Transcript

David Wilder

It's Friday 12th of January and this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. I'm David Wilder, Editorial Manager. Coming up, the US as a global energy supplier: it's big and why it's only going to get bigger. But first, Neil Shearing, our Group Chief Economist, is with me once again to give us the lowdown on the big macro market issues. Hi there, Neil. How's it going?

Neil Shearing

Hi, David. Good. And you?

David Wilder

Yeah, yeah, yeah. End of the week. But lots to talk about. We've got to start with the headlines. It's become a bit of a cliche to say we live in a more dangerous world. Now we have on the front page of every paper a US-UK attacks on Houthi positions in Yemen. They're coming on the eve of Taiwan's election. Our take on that vote is whoever wins. The question of Taiwan's status is going to remain unresolved. There's rising tensions in the South China Sea. War in Ukraine continues. No real sign of an off ramp there. I could go on. We said in 2022 that geopolitics is back as a driver of the global economy, but what does this all mean for investors? I mean, yeah, it's a more dangerous world, but how do we factor that into decision-making?

Neil Shearing

Yes, you're right. I think it stands to reason it's a more dangerous world. We can see that, as you say, just by looking at the headlines. It doesn't really help you think through the macro or indeed the market consequences of that new world though -- it's more of a statement of the obvious I would suggest. Now, one channel through which this will have an immediate impact on the macro and the markets is through energy markets and the impact on energy prices given that the latest flash point is happening in an oil-producing region and is obviously disrupting oil flows. We've seen for example as we talk on Friday morning London time Brent crude just go above $80 a barrel, it's up about 4% already today. So that's the immediate way in which I think this more dangerous world is affecting macro markets is coming through energy prices and perhaps more volatile energy markets. But that's really a function of where this latest conflict is happening. It doesn't help you think through, for example, the impact of Taiwan's elections -- or indeed the US elections for that matter -- in terms of the geopolitics. I think the better way to think about that is the framework that we set out, as you say, a couple of years ago in our work on geoeconomic fracturing. Subsequently, the IMF's called it ‘geoeconomic fragmentation’. But it's essentially this idea that having been through two or three decades of integration, that we're globalizing trade integration, capital integration, labour integration, now actually what's happening is because China has emerged as a strategic rival to the US rather than a partner, the world splitting into two blocks, one aligned with the US, one aligned with China. That gives you a framework, I think, for thinking through the macro consequences of this more dangerous world.

Now, does that mean that we're going to get de-globalization with supply chains severed and production moving back to the US or Europe from China? No, I don't think it does because there's no good geopolitical reason for all of that production to shift. However, it does mean that there will be more flashpoints between the two blocks and Taiwan’s elections is a good example of that.

David Wilder

Ok so a global economy splitting into these competing economic blocks. Take that a step further and talk about those blocks and how that feeds into looking at this quote unquote more dangerous world.

Neil Shearing

Well, I think one point to make is that the composition of these blocks is fluid. Could, for example, be influenced by the outcome of the US election later this year, perhaps we can get into that. But as things stand, our analysis suggests that the US block pulls in Europe, Mexico, Korea, Japan, countries like India lean to the US as a sense in which China might start to use the BRICS as a bulwark against Western power. But actually a lot of people pushing that argument forget that China and India actually have an active conflict along their border. Our analysis suggests that India tends to lean towards the US rather than to China. So, when we take account of economic relations, political relations, financial relations, that the US bloc is both large in terms of a share of global GDP, but it's also pretty economically diverse. Within that, you've got some low-cost manufacturers, you've got service based economies, you've got high-end manufacturers in the advanced world like Korea and Japan, you've got most countries in Europe. Conversely, if you look at China's bloc and which countries tend to align there, they are by and large relatively small economies. Russia's the largest. They tend to be autocracies, but most importantly, they tend to be commodity producers. So the size of China's bloc is smaller in terms of GDP, but I think as important, it doesn't have the same amount of economic diversity that the US bloc does. That's important when we start to think through the challenges posed by fracturing and the ability that different blocs have to flex in order to meet those challenges. So if you think, for example, about high-tech goods production being moved out of China, well that could be done in another low-cost centre like Vietnam that aligns with the US. But when it comes to knowledge flows in particular going in the other direction from the US and China, it's difficult for China to find a substitute for those within its bloc.

David Wilder

I guess it's important to stress though, this isn't a zero-sum game and that a lot of the trade that's going on between the blocks, specifically between China and the West in terms of manufacturing exports. And all that's still going to continue, isn't it? Even if we are in a more fractured, dangerous world.

Neil Shearing

Yes, that's exactly right. I think there's a view that we've been through a phase of globalisation. We're now heading into a phase of de-globalisation in which supply chains are severed and there'll be this big reorganisation of global trade. Our view actually is that a lot of that won't happen. That most trade will remain relatively untouched by fracturing for the reasons you suggest. There's no geopolitical implications of a lot of trade of say low-end consumer goods. It just doesn't matter from a geopolitical perspective. So I'd push back a bit on this idea that a more dangerous world means a world where there's substantially less trade.

David Wilder

I want to pick up on what you said about the US election because the Iowa caucus is on Monday. That's the day this podcast goes out. It's kind of seen as a starting gun for the US election. I don't want to get into who we think is going to win in November. We don't take views on that. But I would like you to talk a bit about what a potential Trump presidency, part two, could mean for this dangerous world, geoeconomic fracturing narrative.

Neil Shearing

I think the short point is it could have major implications. As I was saying, that the US bloc is both large but also economically diverse. And the reason it's economically diverse is because a host of countries from Europe and Latin America, from East Asia. But if there was to be a shift inwards towards a more isolationist position by the US, and I think some of those ties might start to be severed. Now, as you say, we're still many months away from the election, but already we're seeing Trump talk about, say, a 10% unilateral tariff on all imports to the US. That could have a major impact on the relationship between the US and, for example, Europe. And if that starts to create strange intentions within the US bloc, then I think there's a risk that bloc starts to fray and fragments and some of the advantages that the US has in this fracturing world will start to dissipate.

David Wilder

Okay, let's get on to more prosaic matters. Looking at the week ahead, among the big data releases is UK CPI. You predicted in last week's podcast that the US CPI release would suggest a pick-up in inflation, give markets a bit of a scare, and that's pretty much what happened. Is there a risk the UK one does similar?

Neil Shearing

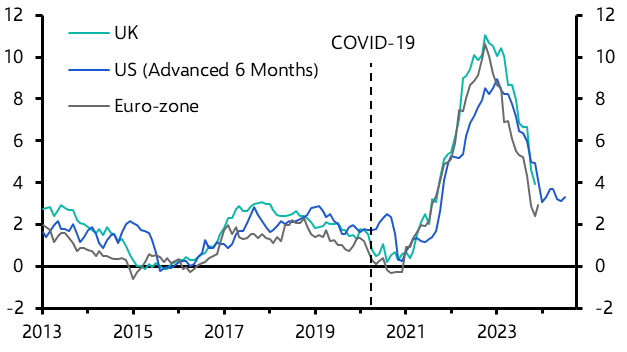

Perhaps not this month, but I think it's going to be a pretty rocky path on headline inflation in the UK over the next couple of months. So we've pencilled in a fall in headline inflation from 3.9% in November to 3.8% in December. But much like the US, there's some pretty unfavourable base effects hitting around the turn of the year. So in January's data, CPI data in the UK, we think it nudged back above 4% because of these base effects. Now, the Bank of England is going to be focusing principally on core inflation, just like the Fed is focusing on core PCE. On that front, we think that core inflation in the UK will be broadly unchanged at about 5.1% in December. Now, over the past week, we've also had Governor Bailey testifying to lawmakers in parliament talking about the potential inflationary consequences of tensions in the Red Sea, the impact on energy prices, and the feed through to UK inflation. I suspect that's a bit overdone, there I say. The big picture is that over the next couple of months it could be a pretty rocky path for UK inflation, but by the time we get to April, we could get a big fall, perhaps to below 2%, the MPC's target. And that in turn, I think, will pave the way potentially for rate cuts by the middle of this year. We've penciled in a first move in June.

David Wilder

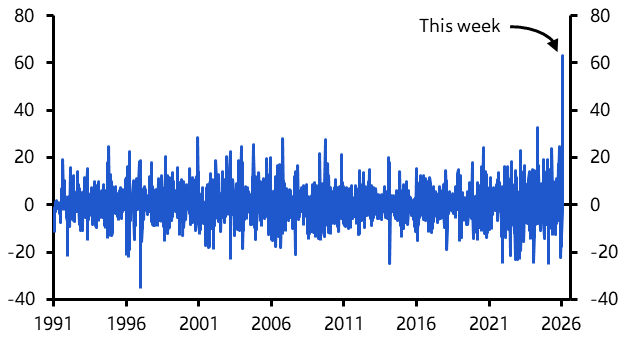

BlackRock Strategist was out over the past week talking about how they'll be back to punish the Tories and the Labour parties going into the UK election this year. Now, Ed Yardeni coined this term “bond vigilantes”. He was saying back in October when the 10-year US Treasury was about 5% that they were back. Since then, yields have tumbled and actually auctions over the past few weeks show that investor demands for DM bond issuance is very strong. So where are the vigilantes?

Neil Shearing

It might be one of those cases where both things can be true at the same time. On the one hand, you're right, although yields have backed up a bit since the start of this year, the big picture is that over the past couple of months they've fallen substantially. So we have both US 10-year yields under 4%, UK yields also comfortably under 4% at the moment too. However, I think the point about bond vigilantes is not so much about the ebb and flow week to week, month to month of bond yields -- at least in my view -- it's more about the scope or the latitude the bond markets give governments when they're setting fiscal policy. Now, for much of the period over the last 10, 15 years in a low rate environment, governments haven't really had to think about the bond markets when they've been setting fiscal policy. The bond markets effectively have been giving them a free pass. Interest rates set by central banks have been extremely low. That's fed through into very low bond yields. Debt servicing costs are not something that governments have had to spend much time thinking about. That is now changing. Now, we think that we're at peak interest rates and that rates will be cut across DMs over the course of this year. That will pull down, I think. But by the same token, fiscal positions are looking pretty stretched in a number of countries. If you look at the government budget deficits, for example, given that most economies are still at full employment, they are substantially larger. Two to three percents of GDP larger than was the case before the pandemic. So there's been this structural loosening of fiscal policy. We're in a higher rate environment. I don't think that precludes bond yields from falling over the course of this year's central bank's cut interest rates. But what it does mean is that any new government or indeed incumbent government has much less room to loosen fiscal policy. They're going to be kept on watch by bond markets. I think governments across the DM world are going to have to be tightening fiscal policy in a kind of structural way over the next two to three years.

David Wilder

Neil Shearing there on fiscal risks in 2024. We've got a whole page dedicated to this issue on our website, including new in-depth report on Japan's public debt situation. I'll link to it on the podcast page. On those attacks on Houthi positions, our Commodities team looks at that in their weekly wrap. I will link to that in the podcast page. It's got some important points to make about the response from oil versus gas markets. It looks at risks ahead. I'll also link to our recent note on the global inflation implications of these disruptions to shipping in the Red Sea. Again, take a look at those on the podcast page. We'll be continuing to monitor the situation and we'll be alerting clients with timely analysis of what it all means for markets and the global economy. Neil talked about that UK CPI release this coming week. There's also new UK labour force survey data on Tuesday to watch out for and on Wednesday China releases its Q4 GDP figures. We're expecting to see a slight pick-up in activity to 5.5% in year on year terms versus 4.9% in Q3.

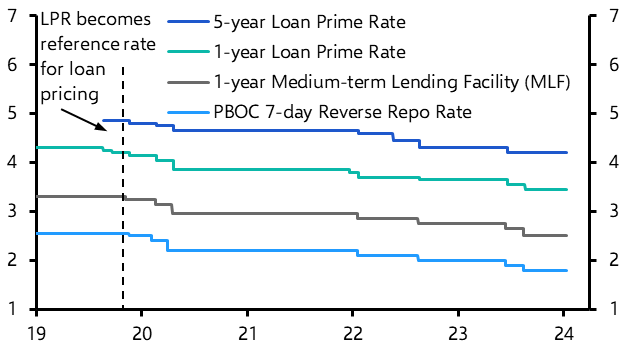

This is a story that's better told by our own China Activity Proxy, that's our alternative growth measure and it tracked a slight improvement in October and November. Our China team sees things getting a bit better in these opening months of 2024 on the back of policy easing, but also warned that this situation won't sustain, risk of a downturn is going to build as we head through 2024. Watch out for their coverage of the data, that's this Wednesday and I'll link to their preview of what's coming on the podcast page. Now, the US last year became the world's biggest exporter of Liquified Natural Gas or LNG. This is a watershed moment in the global energy market and according to Bill Weatherburn from our commodities team there's much, much more to come. He's just completed forecasts for US net energy exports and they show them rising a stunning 60% over the coming five years. I spoke to Bill earlier in the week about what's driving this and what it means for the global economy. I started by asking how the US became such a big player in global supply.

Bill Weatherburn

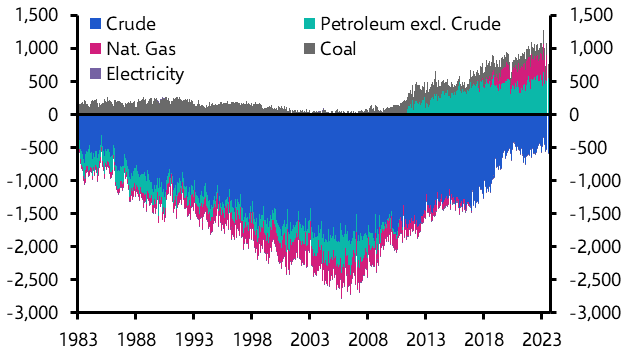

In 2022, US net energy exports, which is exports minus imports, were about 5.8 quadrillion British Thermal Units, and that was 70% higher than in 2020. And the key reason for this is that in the last 10 years or so crude oil and natural gas production has risen dramatically due to improvements in drilling and extraction technology. This has reduced the need for imports and allowed the Obama administration to actually lift crude export bans in 2015. These have been in place since 1975. More recently, the completion of several LNG export terminals has meant that not just oil products but natural gas exports have soared.

David Wilder

Okay. Let's go straight on to LNG. You just touched on there the build-out of LNG infrastructure. But talk a bit more about the big drivers of the increase that you see coming over the next five years.

Bill Weatherburn

Well, the export of natural gas is really governed by these liquefaction terminals. And they take a fair amount of time to build. But based on current plans, export capacity in the United States should rise by a further 60% over the next five years. These plants are most likely to operate near full capacity because natural gas prices in major foreign markets are much higher, and this makes it more profitable to sell offshore than in the US. For example, natural gas prices in Europe are about five times that in the US. It is also important to stress that LNG exports are almost certain to rise for very different reasons. Petroleum products such as gasoline and diesel, these exports should also rise as well, but we don't ever expect the US to be a net exporter of crude oil. Currently, the US imports around 2.7 million barrels per day of crude of more crude than exports. This is much less than it used to because as crude production has risen, imports have fallen and exports have risen as well. But many US refineries are more efficiently run using heavy crude grades, which the shale sector in the United States does not produce. So some crude oil will always be imported. And furthermore, domestic crude production would have to rise considerably for the US to export more than it imports. We're talking quite sizable increases in production and something that we don't think they're going to be able to achieve if, as we expect, global oil prices start to fall. Global oil prices have come under some downward pressure recently, but we think they'll come under further downward pressure as producers in the Middle East ramp up their output in order to exploit oil reserves while oil demand is still rising. And this should weigh on US crude production, which in turn should weigh on US exports of crude.

David Wilder

Getting back to LNG for a second, I thought one interesting point that you make in your report is that yes, we're going to get this increased infrastructure to refine and store more LNG. There are these domestic demand shifts that are also going to play a big role in driving US energy exports. Talk a bit about them.

Bill Weatherburn

Yeah, I think that's one of the more interesting dynamics is that the more the US reduces its own consumption of fossil fuels the more it can sell to the rest of the world. So coal is actually probably the best example of this. I mean, both production of coal and consumption of coal in the United States has been declining for over a decade, but consumption has fallen faster due to a switch to natural gas for generating electricity and in the future, greater renewables will eat into coal's use of electricity generation. But this has left more coal available for export. And the same is true for refined oil products, again, like gasoline and diesel. So as the US consumer buys more electric vehicles and due to general improvements in combustion engine vehicle efficiency, there should be more refined oil available for export.

David Wilder

You spoke earlier about oil exports taking off on the back of the Obama administration lifting curbs in 2015. Politics is a big risk factor here, isn't it? You've got this big surge in US exports in the coming five years on the back of an already stunning increase. But we’re at the beginning of an election year, November is looming. How could the outcome of the US presidential election change your story?

Bill Weatherburn

Yes, that's really interesting. The US presidential election looms larger over all aspects of US policy, but energy and the environment will be major battleground issues. I think the key point to make in terms of energy trade is that the outcome of the election will matter more for US fossil fuel consumption than production. Oil and natural gas production is already at record highs, as you said. It's possible that a new administration might be able to give production a little bit more of a boost by opening up some federal lands for drilling or undoing bans on drilling in the Arctic Circle, for example. But global oil and natural gas prices are going to be the biggest drivers for their investment, not changes in policy. In contrast though, if a new administration comes in November and removes certain policies that encourage electric vehicle sales, for example, or weaken rules around vehicle fuel efficiency standards, then US oil demand is going to be higher over the next five years. And if oil demand is higher, then net exports will be lower, or at least lower than we currently forecast they'll be. Apart from oil, I think there's a risk a new administration could improve new LNG export terminals more quickly. This is an upside risk to our forecast because natural gas exports would be higher and as would US domestic gas prices.

David Wilder

Let's take a big step back because we've already last year had the US becoming the world's biggest LNG exporter. Five years out you have another big rise in US energy exports in your forecast. What are the big takeaways here for the global energy markets and for the global economy?

Bill Weatherburn

Firstly, sharply higher LNG exports will bring US domestic gas prices in line with the higher prices in Europe and Asia. And this is going to undermine the cost advantage that many US businesses have enjoyed in comparison to businesses in Europe. But more significantly, the US is going to be an increasingly large supplier of fossil fuels to global markets. And if you look back at our work on global economic fracturing, which at its heart has the view that the global economy is fracturing into competing US aligned and China aligned blocs of countries, the US block already has significant economic advantages that rising energy supply from the US reduces the ability of other countries to use energy as a weapon.

David Wilder

Bill Weatherburn there on another surge in US energy net exports. The fracturing work that he and Neil earlier referenced is all on a dedicated page of our website. I'll link to it in the podcast notes. We're continuing to add new analysis, including our look at the risks around Taiwan's election, which went up this week. Depending on when you're listening to this, you can tune into our live post Taiwan election online briefing, what we call a ‘Drop-In’ or listen into that recording. The session is being held on Monday 15th at nine in the morning, London, five pm Singapore. That's a little earlier than the original scheduled time. You can find details for that and for all of our online and in-person briefings on our events page capitaleconomics.com/events. That's capitaleconomics.com/events. Remember, if you are a CE Advance client, you get access to all our briefings, all our analysis, all our data and much more besides. That's all for this week. We're back next week with much, much more on the global economic outlook. Until then, goodbye.