Plus, an exclusive clip from our recent client briefing about Russia's presidential election explains why its economy has proven so resilient to sanctions and outlines what to expect from another six years of Vladimir Putin.

Transcript

David Wilder

It's Friday, 15th of March, and this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. I'm David Wilder. Coming up, an exclusive clip from our client briefing about the Russian presidential election and the state of Vladimir Putin's war economy. But first, I'm pleased to say that Neil Shearing, Group Chief Economist, is back after weeks on the road talking macro and markets with clients. Hi, Neil. Good to have you back.

Neil Shearing

Hi, David. Good to be back.

David Wilder

Lots been going on recently. But we've got to start with our old friends inflation and central banks. I feel like a bored nine-year old in the back of a car every week. I'm asking, "are we there yet?" but we've had markets in a mini panic in recent weeks/days over some hot-ish US inflation numbers. What do you make of all this data? How hard is the journey back to 2% looking? Are we there yet?

Neil Shearing

Yes. And increasingly, I feel like the grumpy parent saying "no, we're not quite there yet. There's a bit further to go". And I think that's what the data over the past few weeks have been telling us. I don't think that means to say, by the way, that we won't get there. And indeed, our forecasts are still that core inflation in most major advanced economies is kind of back at central bank targets and levels they're comfortable with by the end of this year. But I think the journey down to that kind of those 2% targets was never going to be a smooth one. And indeed, the data from January or February that we've had have supported that. So, obviously the US CPI numbers over the past week are the latest piece of evidence that inflation has proven to be a bit sticky. The PPI numbers over the past couple of days, they surprised on the upside. Two, obviously it's PCE inflation the Fed really cares about and we'll get data on that towards the end of this month. We're going for 0.3 % month-on-month increase in core PCE in February, which again is a bit too strong for the Fed's comfort and probably pushes back again, expectations of rate cuts. We're still sticking with June, but I think it is the case, you're right, yhe data over the past couple of weeks or so have generally been a surprise to the upside on the inflation front. And that does, I think, support the idea that we're looking at summer cuts rather than spring cuts. And I think it's probably fair to say that the timing of those cuts probably pushed back a little bit, maybe at the margin.

David Wilder

Yeah. Let's talk about those rate cut expectations. As I said, the market scaled back when they expect the Fed to start moving. Then we've had Fed officials like Kashkari and Bostic Bostic pushing back even on those diminished expectations. The Fed meeting this coming week, what are the chances that the rhetoric from the FOMC and from Powell's press conference afterwards reflects some of this hawkishness?

Neil Shearing

I think there's a good chance. I mean, the rhetoric from officials has kind of been all over the place in recent weeks. Powell taking a slightly less hawkish tone in his semi-annual testimony to Congress. But then as you say, we've had more hawkish comments from the likes of Philip Jefferson, Christopher Waller over the past few days. So the rhetoric I think has been a bit all over the place. I suspect there might be a bit of a hawkish pivot in some of the rhetoric at the meeting over the next week. Of course, we'll get new dot plots as well. The market will be clearly focused on what those are telling us. We're sticking with the idea that Fed officials will be forecasting 75 basis points of cuts this year. But clearly any change to that is more likely to be in the direction of 50 basis points cuts, I suspect. And if that was to happen, then that would obviously have big ramifications for the bond market. For what it's worth, we're sticking with 100 basis points of rate cuts in 2024 as a whole.

David Wilder

What about this view in the market that actually there won't be any rate cuts at all from the Fed in 2024 that are re -accelerating US economy? I mean, talk about the risks around that view.

Neil Shearing

Well, look, it's clearly possible, but I think we need to see a shift in both the real activity data and the inflation data in order for that to happen. The key point that we keep stressing in client meetings is that the Fed funds rate at the moment is at five and a quarter to five and a half percent. As a result of the PPI data we've had over the past few days, we think that core PCE in February will be at a six month annualized rate of about 2 .9%. So let's say 3%. So the real interest rate in the US is something like two and a quarter to two and a half percent. That is still extremely restrictive. We can argue about where the so-called neutral real rate lies. As we discussed on this podcast before, it's a useful analytical concept, but it's not much useful in terms of actually guiding policy because it's very difficult to pin down. But there's very few estimates that would suggest it's as high as two percent, let alone two and a half percent. So the point being that the economy is going to have to be a lot stronger, I think, and inflation a lot stronger too, in order for there to be no rate cuts this year, given just how restrictive policy is at this stage and just how much inflation has already come down. So yeah, it's possible. Maybe we get a much more resilient economy. Maybe it turns out the labor market doesn't quite cool in the same way that we're anticipating it to, or the forward-looking indicators suggest it will do. Maybe there's even greater fiscal support than this year, perhaps coming through. So it's possible, but at this stage, unlikely.

David Wilder

We've had questions coming in from clients this past week and from journalists asking whether the European Central Bank or Bank of England could wind up cutting interest rates before the Fed does. Now, the BOE meeting is this coming Thursday. We've just had the ECB meet. What's the mood music around this in terms of timing? Do you think the Governing Council and MPC are worried about inflation risks if they go first?

Neil Shearing

Yes. With one or two exceptions, I don't really buy this idea that other central banks need to wait for the Fed to move in order to provide them cover to adjust interest rates. So for example, we think that over the next week, the SNB, the Swiss National Bank will cut interest rates because domestic conditions in Switzerland, very low inflation, warrant that move. And that's even more the case when you think about the ECB. The eurozone is a major economy. The ECB is a major central bank. It has the scope to set interest rates according to domestic conditions, a monetary policy according to domestic conditions. And indeed, it has moved and acted independently of the Fed in recent years. So for example, in 2011-12, it cut interest rates while the Fed had kept policy on hold because domestic conditions in Europe warranted that move. So the key question in my mind is do conditions in the eurozone warrant a rate cut? And if you look at what's happening in the real economy, I think you can make the case that yes, it's in need of more support than the US. The eurozone economy essentially flatlined over the past 12 months, Germany in recession compared to the US where economic growth has been obviously much stronger. On the inflation front is a bit more of a mixed picture inflation coming down quite nicely, but that's mainly about goods inflation, services inflation has come down, but there's some signs in the recent data that that's now starting to stall. So, to my mind, the key question is, does services inflation resume its downward trend and continue to fall in the eurozone over the coming months and quarters? Our view is that it will do, and that's why we've penciled in a June rate cut by the ECB, but to the extent that the ECB doesn't cut in June and it cuts later, I think that's likely to be because domestic inflation has not fallen as far as we expect over the coming months, rather than the fact that the Fed's delayed cutting and therefore not provided cover for other central banks, including the ECB, to start loosening policy.

David Wilder

From rate cuts to rate hikes, the Bank of Japan meets on Tuesday. We've got a forecast for a rate hike at that meeting, what would be the first since 2007. But it's a one -off hike, 25 basis points. So what's the strategy around policy here and what will markets make of it?

Neil Shearing

Yeah. So as things stand, as we're talking the consensus of analysts is that the first move will come in April. We think actually, as you say, it will come at the next BOJ meeting over the coming week. Why do we think that? A large part of our thinking is informed by the outcome of the spring wage negotiations, the so-called Shunto, which has seen the largest increase in wages this year since 1991, 5.3 % average increase that includes some seniority payments. So if you strip those out and look at underlying, it looks like it's about three and a half percent on our estimates. So again, the largest since the early 1990s. And enough interestingly, to prompt the Japanese government to declare over the past week, the end of deflation. Now, we've been here before, of course, and the BOJ has in the past, tightened prematurely only to tip the economy back into deflation and that's why, although we expect a move over the coming week to get out of negative territory, I don't think this sets us up for the start of a very aggressive rate tightening cycle. So if you're a central banker, you really don't want interest rates in negative territory. You've got 2000 years of financial history that tells you that that's an anomaly. And if you're a Japanese central banker, though, you have to be a bit careful that you've tightened before and you've tipped the economy back into recession and exacerbated the problem with deflation. So our view is that the BOJ may be one and done. In other words, they take this window of opportunity before other major central banks are cutting rates to get out of negative territory. But because of this kind of persistent concerns about deflation lingering in the background and because although this year's wage negotiations have been strong, underlying wage and price dynamics, although stronger than they have been over the past decade, they're still pretty weak. I think it may be a case of, like I say, one and done, which is again, a bit less than the markets are pricing in. So we're pricing in a faster move, a more immediate move, but ultimately less tightening than the markets are pricing in.

David Wilder

Let's step back a bit from the inflation central bank dynamic and talk TikTok. The House of Representatives over the past week have moved to ban it. This is the short video app whose Chinese ownership structure has US officials worried. The bill passed in the House with 352 votes. That tells you either Congress has had enough of trying to get their kids and grandkids away from screens, or that opposition to China is perhaps the last bipartisan issue in Washington. But TikTok isn't semiconductors and it isn't tech hardware. So why is it in the crosshairs of the US government?

Neil Shearing

Yes, we can add TikTok to the long list of things that we didn't think we'd be talking about on this podcast. And I think it's not really that significant from a macro perspective either, dare I say it. I do think it says something interesting about US -China fracturing and how that is likely to play out. One view is that the world's deglobalizing, that the US and China are pulling apart, and that as a result of this deglobalization, we're going to see supply chains reorientating and production reassured to the world's major advanced economies. We've never really bought into that view. Indeed, we published a major report over the past week analyzing just what's happened in the US and find that there's almost no evidence of reshoring of manufacturing to the US over the past decade. However, I think what's happened with TikTok is a much better illustration of how fracturing is going to play out. So although it would be great to get the kids off of screens, that clearly isn't what has driven this decision or motivated this move. It's about data and security. And I think that is going to be a key element of US-China fracturing. The fault lines are going to be around things like data, technology, semiconductors, obviously, batteries, biotech, all of these issues that have national security implications. So these will be the fault lines along which fracturing evolves. This is a good example of how it's going to affect our everyday lives. So it will affect the phones that we use, the cars that we drive, and the social media platforms that we're able to engage with. So it's a good real-life visualization, I think, an illustration of how fracturing will affect everyday life.

David Wilder

And what about Donald Trump in all of this? He was initially in favor of a ban. He's flip-flopped on that. He's now opposed to a ban. It was unpredictable, dare I say it, erratic, his approach to this issue. Is this a harbinger of Trump 2.0 in the event that he wins come November?

Neil Shearing

It's always difficult to interpret just what's going on in the mind of Donald Trump and what that means for policy, clearly. But I do think you've hit upon something there. It reminded me at least of just how erratic policymaking was between 2016 and 2020. I was based in the US at the time and I remember we would get up at 6am in the morning East Coast time and check Twitter would be the first thing you do to see what the president's tweeting about, see if it affected the Mexican peso or particular stocks. Clearly Twitter or X has fallen out of favour with Trump in the meantime too, but it's a good reminder, I think, of the fact that policymaking was erratic and it did have real market implications, at least in the very short term. And maybe TikTok's another example of that erratic and more unpredictable policymaking and just a reminder of how we might return to that.

David Wilder

Neil Shearing there on the potential return of Donald Trump on the latest lurch in the fracturing of the global economy and a very busy week ahead in central banking. He mentioned a report on US jobs reshoring, which I'll add to the podcast page, but which you can also find on our growing hub of analysis around the US election. On central banks, watch out for all our coverage of the BOJ, the S&B, the Fed, the Bank of England meetings. The RBA is also meeting on Tuesday. We'll have analysis out about that decision. We're holding Drop-Ins in the coming week. These are our short-form online briefings. There'll be one shortly after the Bank of Japan meeting on Tuesday and after the Bank of England meets on Thursday. That Thursday session will take a comparative look at the March ECB, Fed and BOE decisions. I'll post details of those on the podcast page. Also this coming week, watch out for UK inflation data. That's due Wednesday, so a day before the BOE meeting. Our UK team's forecasting a big leg down in headline CPI for February and thinks it'll be just over 1% by May. So that really would mark a huge shift in the inflation narrative. Paul Dales, who's our Chief UK Economist, is going to be on that Thursday Drop-In to talk about the inflation outlook so do sign up for that session to ask your questions and learn more.

Now, by the time this podcast goes out, Russia's presidential election will be over. No prizes for guessing who the winner's going to be, but the prospect of another six years of Vladimir Putin does throw up a host of questions about the direction of the Russian economy, about Russian diplomacy in a fractured world, and about who comes after Mr. Putin. All these questions were tackled in an election preview by Liam Peach from our EM team, and he also appeared on a Drop-In this past week to brief clients and take their questions on the outlook for Russia.

Here's an exclusive clip from that briefing and it tackles two key questions. Why has Russia's economy proven so resilient since Mr. Putin started the Ukraine war and where does the economy go from here? You'll also hear from Chief EM Economist William Jackson, but the clip begins with Liam explaining the impact of sanctions on the Russian economy.

Liam Peach

There was a very polarised debate in the first year of the war about the impact the sanctions really were having. I think a lot of people jumped to the conclusion that sanctions were causing a lot of harm in Russia's economy and clear signs of that. But I think even now, the debate remains quite dishonest really about how the sanctions are impacting Russia's economy. I think first of all, let's be clear, sanctions have had an impact. Some of the financial sanctions that the US has imposed on Russia caused quite a lot of an impact. And Russia's been forced out of international capital markets. It's no longer borrowing externally. It's coming to deleverage and repay its foreign debts. A large part of that is that the Russian government is now having to depend more on the domestic financial system to absorb bond issuance. And that's causing its own problems in Russia because a lot of Russian banks seem reluctant to want to absorb all of the debt issuance. And interest rates on Russian debt are quite high at this point. So that's pushing up debt interest costs. That's causing some impact there. And of course, the rest of imposing sanctions and restrictions on technology exports to Russia.

Russia is importing a lot less technology than it was before the war. So those sanctions have had an impact. I think you've pointed to two areas really where there have been what we've learned to really over the past two years. One is that sanctions in general have been quite porous. I think it's become clear over time that Russia's economy has adapted fairly well to sanctions and it's using loopholes, workarounds, all kinds of circumvention measures to try and get around sanctions. And one of those that's talked about most often is Russia's imports of goods through third countries. And we can look at this in Eurostat trade data. Eurostat exports to countries neighboring Russia. So the likes of Kazakhstan, for example, other Central Asian countries have really surged since the start of the war. It is hard to enforce these. These trade and financial flows are particularly complex. There's a lot of leaps in the chain. It's not easy to stop these, but they are happening. It does seem that there are some banks and firms out there that are willing to take the risk and obey these sanctions. I think the other point worth mentioning is that the lack of a global cooperation of Russian sanctions, I think, is, is working Russia's favor. I think because Russia has been able to export or reorientate a lot of its energy exports away from Europe towards the Asia, that's helped. There are a lot of banks in the Middle East, Turkey as well, that are facilitating Russian international transactions. This has all helped as well. So I think that the lesson there is that sanctions policy on such a large economy as Russia really needs global cooperation to have the film back. And that's just one thing we haven't seen since the start of the war.

William Jackson

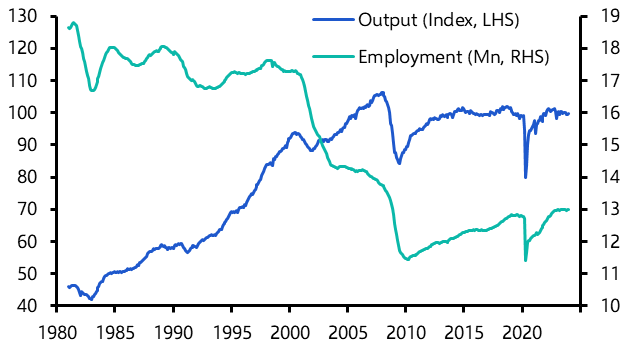

I wanted to turn the discussion a bit more to what might happen to Russia's economy in the years ahead. We've seen really strong growth rates in Russia's economy in the last few years, better than being expected as it's been able to ride out sanctions.

Liam Peach

Yeah, I think that if we've been surprised by anything over the past year or so, it's been the strength of Russian GDP growth. It came in at 3.6 % in 2023. In the fourth quarter, it probably came in at 5 % year-on-year. So rates of growth you don't tend to see in Russia these days, or at least we haven't seen for more than a decade. I think if we were to say, is that growth sustainable long -term, I think everyone's of the opinion that no, it's not sustainable. Russia can't grow at such a pace for very long. It does have structural factors that are weighing on its economy. We think long-term growth is around one and a half percent. I think short-term Russia probably can continue to grow at rates of three to four percent, particularly this year. That's our forecast. The question though is really about what kind of imbalance has come alongside that. Wherever we look in the data, Russia's economy seems to be overheating. The unemployment rate is almost two and a half percent. It's the lowest it's been in Russia's post -Soviet history. There are supply constraints all across the economy. So it's no surprise really, I think, that we've seen such strong GDP growth being supported by new fiscal policy come alongside rising inflation and rising wage growth as well. I think the question for this year and next really is about how this plays out and particularly how fiscal policy feeds into this. As I mentioned earlier, it looks like Russia may impose a larger mobilization in the future. It does look like it's stepping up its war effort and it's spending a lot more money. So I think the question really is that if Russia receives additional fiscal stimulus through the war, is there going to be sufficient non -war fiscal time to help offset that? I think we've got monetary tightening on the one hand, which is helping a lot of the central bankers raise interest rates aggressively up to 16%. That will take the heat out of the economy. But I think the big question really for Russia is map economic stability. And when I mentioned that, I mean Russia achieving low inflation, stable exchange rates and some sort of a broadly balanced budget position. I think that will need to come alongside non -war fiscal tightening after the election.

So I think our baseline forecast, if I were to summarize, is that this year could be characterized by fairly strong growth, pretty high inflation, further currency weakness, but there will need to be some kind of slowdown that takes place in 2025 driven by non -war fiscal tightening to help alleviate some of these macro imbalances. If this doesn't happen and Putin steps up the war effort, the finance ministry doesn't offset that with normal tightening. I think then these pressures just become larger in Russia, stronger growth, stronger inflation and much larger currency depreciation going forward.

David Wilder

Liam Peach there talking to William Jackson about the Russian economic outlook. The full briefing includes talk of de -dollarization, relations with China, Russian crude exports and much more. I'll post a link on the podcast page along with a link to Liam's report. But that's it for this week. Don't forget that all of the analysis and events referenced in this show are available as part of a CE Advance subscription. That's our premium platform. Details on our website at capital economics dot com forward slash CE hyphen advance. That's forward slash CE hyphen advance. I'm out next week, but Neil will have a special guest on to talk about one of the big issues in global macro. You really won't want to miss this one. Check it out next week. But until then, goodbye.